Roma is a semi-autobiographical film where we witness a series of scenes inspired by the director’s upbringing in 70s Mexico. Presented in nostalgic black-and-white photography, the life of a middle-class (or upper-middle-class if you like) family sets the film in motion and the first 30 minutes are very impressive in portraying the daily routine of the family members in their bustling, spacious house in the Roma neighbourhood (hence the name of the film).

This is a film where the black-and-white photography often seems to be the main performer, super-stylised, bold and imposing. Just try to imagine the following scene: a roof where a housemaid is doing the family laundry while singing and listening to music on an old radio, with children running around, chasing each other. As is usual in these cases, the game ends up in disagreement and bitterness, with the youngest boy lying down under the sun, pretending to be dead. Right away the housemaid does the same, showing her sympathy to the young fellow. Meanwhile, in the background, we witness housewives doing the laundry on other rooftops, we hear neighbours shouting, dogs barking — we can, in a sort of way, smell the odour of the wet laundry. No matter how hard one tries to get the above description accurately, one simply fails to achieve the eloquence with which Cuarón brings the nostalgia of the period to the fore.

There are, in fact, times when the detail and elegance of the director’s images leave one breathless as he paints the melancholy of those years on his black-and-white canvas. The camerawork inside the house is also highly impressive, involving lots of single-shot tracking scenes while the staff and family go around doing their errands. Cuarón seems to know well the secrets of the great auteurs of the past and his obsession with tiny details is telling, be it when he’s focusing on the parking of the car in the small garage or when observing the various planes flying by in the background (which apparently have been naturally captured on location by accident).

The main character of the plot is neither the father, nor the mother of the family, not even the children, but the housemaid, named Cleo, a Mixtec woman who is portrayed as being rather shy, unbelievably quiet, characterised by her taciturn reactions to the most bizarre incidents. What she will go through is a plethora of unbelievable events, in only a short period of just a few months. And this is the first clue that hints at the plot weaknesses which start to become obvious after a while into the film. Lets us just say that Roma could have been a successor to Fellini’s neorealism but instead ends up being a series of poorly-knot scenes rising to hyperbole.

All the coincidence and drama that happens within these few months would have taken years to be realised in real life. You name it: there is an earthquake, pregnancy, civil war, fire, murder, threatening — and all this happens, after the first 30 mins, to such an extent that I wouldn’t blame the viewers if they thought that absolutely anything could happen to the main character from then onwards.

It is rather unfortunate that after the impressive opening minutes, the film borders on the verge of bad taste, something that is hidden behind the impressive visuals. When, in one of the opening scenes, one sees the mother crying while saying goodbye to the father, standing in the middle of the street as a marching band is passing by, one really hopes that this will be the first and last pretentious scene in the movie. Alas, the filmgoer will soon realise that this is going to be Cuarón’s way: pretty scenes that simply fail to do anything else than impress. Not only do they not contribute to the development of the plot, but they also fail to engage with the personalities of the characters. This wouldn’t have been a problem if Cuarón had the intention of just visually presenting a set of images depicting that era. However, this doesn’t seem to be the case since he begins dealing with the characters’ misfortunes, whose past remains a mystery throughout.

As an example, let me describe a scene that takes place on New Year’s Eve in a what seems to be a mountain resort where the bourgeoisie is celebrating while the forest is set on fire. While all the middle-class holidaymakers are trying to extinguish the fire, we can hear them counting down to the new year. Right after that, a man dressed in what seems to be a local Christmas animal costume starts singing a traditional song. This scene alone serves as a sample to the exuberance with which Cuarón fills his sets. Such scenes might have some sort of realism underneath but their sheer choreographed staging is simply over the top. The mere fact that the camerawork often favours the most exaggerated elements in each scene is a testament to that. It seems that for Cuarón a plethora of things must be happening in every single scene, all at the same time, for no apparent reason. As mentioned earlier, this might have been a trademark for Fellini but simply does not seem to work here.

And it is when the plot focuses on the life of Cleo, the housemaid, that the heightening of the drama goes beyond what is tasteful (despite employing real doctors, the hospital scene shocks the viewer with its raw depictions — both unsettling and unnecessary). What we’re dealing with is more or less some kind of soap opera plot wrapped in faux arthouse visual style. And talking about style, the gorgeous images often detract from a more honest outlook on what the characters actually feel. It’s really a pity: had Cuarón stuck to the documentary style with the quiet undertones that we witness in the first half an hour or so, he could have created a substantial piece of art.

Despite the overwhelmingly positive reviews, I tend to agree with the minority of those who think that Cuarón only manages to scratch the surface when it comes to unravelling the emotional side of the characters, while at the same time resorting to old-fashioned stereotypes: Why are most men in the film portrayed in such a negative light? Why is the father brushed aside (and why is he to blame)? Even tiny details are left unanswered: there’s so much talk about the dog droppings all over the place, yet no-one seems to be doing anything about it. And, as another reviewer pointed out, I also feel sorry for the poor dog which again no-one seems to care about. Last but not least: why do we have to accept the clichéd image of Cleo as the unresponsive housemaid who seemingly accepts everything and reacts to nothing? And all this happens in a rich, bourgeois family. The New Yorker critic, Richard Brody, has written a comprehensive review where he also remarks on how Cuarón turns the character of Cleo into a stereotype.

Apart from that, the acting is not always convincing (even though it does suit the unconvincing mood of the film) and the direction resembles way too much the work of past auteurs (Fellini’s exuberance, Pasolini’s look at the bourgeois society, the strangeness of Reygadas, Tarkovsky’s depiction of the natural elements). The plot feels weak every now and then, while the realistic sound (here captured in glorious Dolby Atmos) doesn’t offer much to the plot (let us remember, for instance, the innovative use of external sounds in the Bergman films). In all the above technical parts, Gravity was superior.

Lastly, I should note the presence of Netflix behind the production team, and this could perhaps partly justify the need for a more dramatic plot. The film was, nonetheless, awarded the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival, where Head of the jury was Guillermo del Toro, who has even claimed that Roma is one his favourite 5 films ever!

One should go to the cinema and watch Roma for

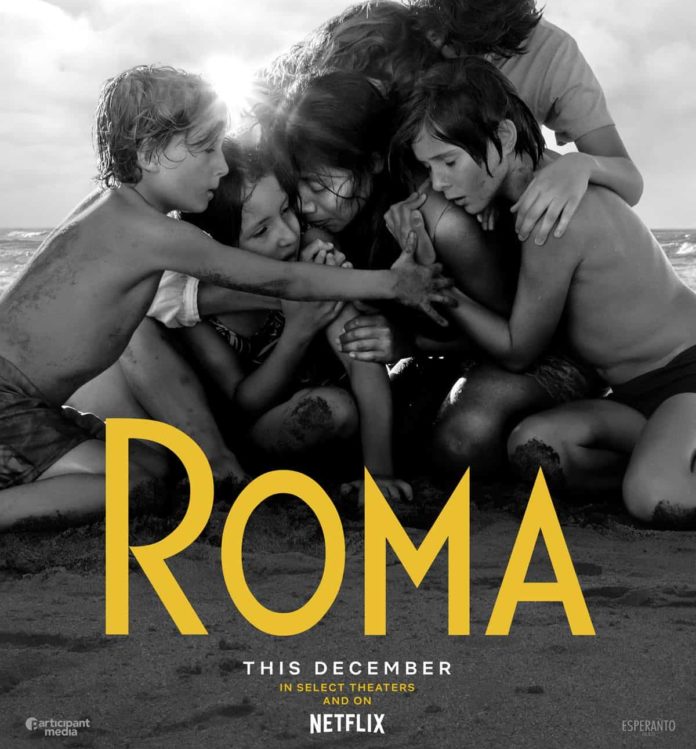

Image: Movie poster/Netflix

With all respect to your opinion, I couldn’t disagree more. I won’t get into detail but the film is highly political -all in the background- and the years before and after marked a tumultuous era in Mexican history, eg. the creation of paramilitary forces used in political life. All this political and social violence is somehow focused in the characters but I didn’t see any mention of these in your criticism.

Thank you for you comment. Yes, you are referring to the Corpus Christi massacre as well as the paramilitary forces that you mention. The thing is I thought that just having these incidents occur in the background does not offer much to discuss. It is as if they are part of the setting the way they are presented, a device to enhance the drama of the main characters if you like. But of course this is only my opinion and I am glad you wanted to share yours. After all, I am sure most people would agree with your point of view, not mine.

[…] most of its Oscar nominations (on a personal level, I thought it was better that the overrated Roma) and my only concern has to do with the morale of the film that shows us how a woman can use any […]