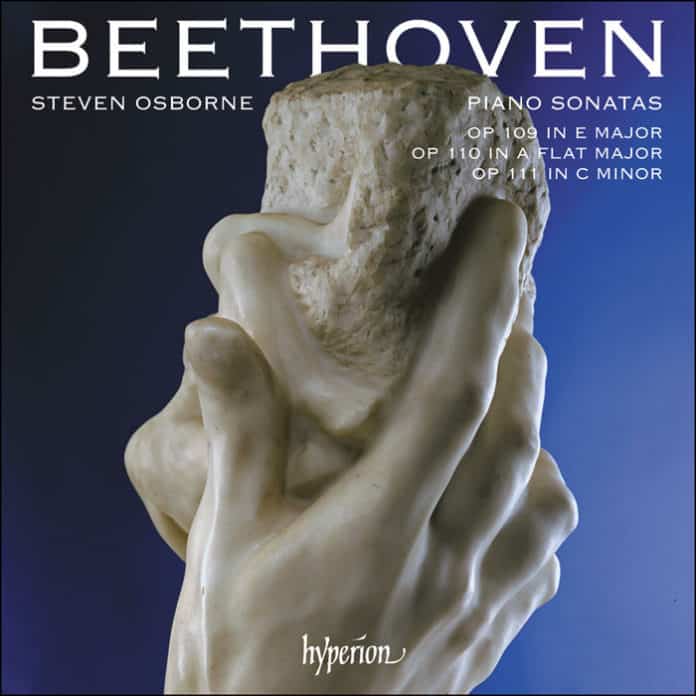

Beethoven, Sonatas op 109, 110, 111 / Steven Osborne (piano) / Hyperion

There are some favourite pieces of art and others that you feel are so otherworldly that transcend the borders of art. For me, and I suppose for the majority of music lovers, the late Beethoven works are among the pinnacles of artistic creation: the Missa Solemnis, the Diabelli Variations, the 9th symphony, the late quartets and, of course, the last three sonatas. For these works, an ideal performance is a rare event and perhaps it would be completely wrong to ask for one. True, such is the depth of Beethoven’s genius that to seek out a single interpretation that attains perfection would be a hyperbole.

Steven Osborne gets very close to that. These sonatas need two virtues: humility and humanity. He seems to possess both. The pianist’s interference should be minimal, for the balance between emotion and sentimentality can easily be tipped — another virtue that Osborne is aware of, judging from this recording.

Take the first sonata of the set, for instance, the lyrical op. 109. The contrast between the dreamy first movement and the Prestissimo second is made even more clear under Osborne. Indeed, his handling of the latter hints at the dramatic contrasts he opts for, adhering to Beethoven’s fast tempo indications. As for the final movement, Osborne provides us with a flowing account of the Andante, where each variation transitions into each other smoothly. It is in the 6th variation, however, where he doesn’t hesitate to go all the way and emphasizes the sense of struggle, giving us an impressive no-holds-barred approach (the other digital alternative that has such an impact on the listener is Kovacevich’s even fiercer interpretation on Warner Classics).

The same ferocity is to be found in the first movement of the op. 110 sonata and I was relieved to finally hear the Allegro Molto second movement played at a faster tempo with particular attention to the antiphonal dynamics. The transition to the contemplative Adagio ma non troppo is almost seamless, the pianist in tune with the Arioso dolente marking. In the Fuga, Osborne is aware of the structural elements that build this powerful finale, and his precise, powerful accelerando brings this extraordinary sonata to a triumphant ending.

And, finally, there’s op. 111 the sonata of all sonatas. The way Osborne plunges into the first movement marked Maestoso – Allegro con brio ed appassionato can only be described as wild and muscular. One would think that after such a ferocious opening the playing could end up sounding muddled, but not here: kudos to Osborne for making every note stand out, the fugue parts both musical and clearly discernible. As for the Arietta, it receives the apotheosis one would expect: from the solemn first notes to the jazzy, boogie-woogie rhythms which here really seem to sing. Listen to them played by Osborne and you will understand why Jeremy Denk has described this music as “proto-jazz”.

And it is after this frenetic dance that the music begins to transcend the boundaries of art and becomes weightless, floating in higher realms. One could say a trill is a trill, but the weightlessness of Osborne’s playing combined with this subtlety of tone is ideal for the spiritual connotations of this music. Often people like to describe loud symphonic as music of the spheres but is it not perhaps in the most intimate passages that a transition beyond the earthly realm is achieved?

The excerpt below, taken from Thomas Mann’s Doctor Faustus, is a testament to the subjective beauty of this music and the effect it has on individuals:

[…] and this added C sharp is the most moving, consolatory, pathetically reconciling thing in the world. It is like having one’s hair or check stroked, lovingly, understandingly, like a deep and silent farewell look. It blesses the object, the frightfully harried formulation, with overpowering humanity, lies in parting so gently on the hearer’s heart in eternal farewell that the eyes run over. “Now for-get the pain,” it says. “Great was — God in us.” “’Twas all — but a dream,” “Friendly — be to me.” Then it breaks off. Quick, hard triplets hasten to a conclusion with which any other piece might have ended.

To sum up, what is it that makes this release so special? First, Osborne’s ability to move from the quietest pianissimo to the loudest fortissimo without the need to show off and his sense of daring as far as the tempo choices are concerned. One can hear the loud passages being loud, the slow movements interpreted without any sentimental excess, and the allegro sections played, at last, fast. When other pianists stand back and hesitate as if these pieces were some sort of fragile swansongs, Osborne steps forward and showcases their inwardness by playing them heroically. It sounds contradictory but it works.

And then there is Osborne’s super attention to the dynamics, how he employs his pedalling with utmost care and the subtle nuances, especially when moving to the pianissimo passages that make the listener catch their breath. This is special indeed. (My only concern has to do with a hardly audible mechanical action from the piano leaving a slight buzzing sound from the Steinway strings, which I noticed only in the quieter passages of op. 110. But most listeners won’t even notice — it is nearly imperceptible and won’t detract from the enjoyment of this stellar release.)

So it seems that history repeats itself when it comes to great interpretations of cornerstones of Western music. Like Schnabel, Solomon, Michelangeli, and Rosen before him, Steven Osborne has achieved the almost unachievable and can now join their ranks. Believe the hype and the accolades this release has received so far: this performance of the last three Beethoven sonatas is one for the ages.

The High Arts Review Gold Rating

[…] Η κριτική μου στην αγγλική έκδοση. […]

[…] Can I say this is the best digital rendition I have heard of the late sonatas? Osborne’s pianism is daring, revolutionary and insightful. Read my full review. […]