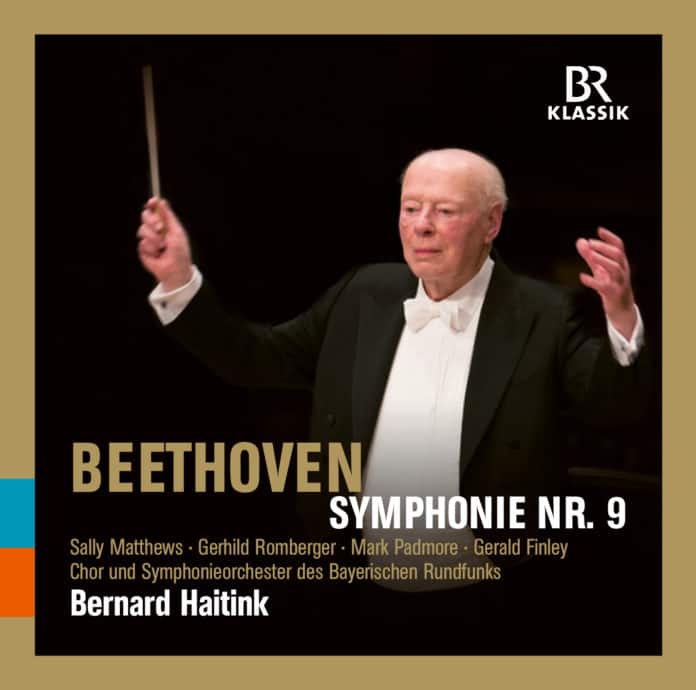

Music review – Beethoven, Symphony 9, Bernard Haitink / Chor & Symphonieorchester des Bayerischen Rundfunks / Sally Matthews, soprano / Gerhild Romberger, alto / Mark Padmore, tenor / Gerald Finley, bass / BR Klassik

This is a stately reading of Beethoven’s 9th. The duration of the first movement alone will surely raise some eyebrows. At 17:19, one could argue this is among the slowest performances to have appeared recently (Haitink’s Concertgebouw recording was just over 16 mins., while his LSO live rendition clocked in at 15:36). Juxtapose this with the 13-minute performance of the Adagio (Haitink’s fastest on record!) and you know you are in for a different interpretation of this over-recorded piece. Of course, timings are not everything but their relationship between movements can tell a lot about the conductor’s grasp of the work.

But let’s take things from the start and how surprised -and relieved- I was to hear the opening string tremolo played so slowly and at a louder lever (in so many recordings it is barely audible) while carrying all the cosmic energy of the mysterious undertakings that are about to evolve. In fact, this slow tempo is one of the three main characteristics of Haitink’s shaping of the first movement. The others are the clarity of orchestral texture and the steadiness of musical development.

To be clear, so static is the unfolding of the first movement -no sharp attacks here, no tempo fluctuations- that one hopes for the recapitulation to arrive soon. And when it does, it is impressive for all its structural transparency, something achieved by few conductors, but without the cataclysmic force of other performances. Such is the complexity of Beethoven’s writing in the recapitulation that conductors either emphasize the string clarity or the overpowering drama – alas, it seems one can never have both (unless it happens to be Furtwangler). And Haitink belongs to the first category, clarity at the expense of power. Even the coda here doesn’t sound like the threatening march that it is in other recordings. Having said that, this is a very classical reading of the Allegro first movement. Noble and imposing.

As for the Scherzo, it follows along the same lines, again more steady than driven. Haitink’s recording with the LSO was brisker and more energetic but I much prefer the characterful strings of the Bavarian orchestra here.

I initially expressed my concern for the duration of the Adagio. I have nothing against swift accounts but as I’ve said earlier, when the opening movement clocks in at 17 mins, it is a curiosity for the Adagio to be just over 13 mins — in fact, this is even faster than Haitink’s own 14 min. account with the LSO (his Concertgebouw recording in the Philips set was over 17 minutes!!!) But how is the music-making? To be honest, I was expecting more transparency here, I felt that some inner voices from the strings are not heard as clearly nor are they as emphasized as in other recordings. However, the beautiful woodwinds of the Bavarian orchestra really shine (and it is no exaggeration to claim that, presently, the Bavarian RSO is one of the best orchestras in the world). The overall impression here is that of an Adagio with a great structural arch and impressive playing, which is perhaps lacking overall in emotional depth.

As for the finale, this is the highlight of the disc and among the finest renditions I have heard in years: big-boned, transparent, communicative, moving. Even the orchestra sounds better here with even more detail emerging from everyone involved – pay attention to the shimmering strings and expressive winds. The playing of the Bavarian forces is so distinctive that you will probably notice details you had missed in other recordings. Add to this some notable singing from the soloists and a precise and feisty choir. And above all, there’s Haitink’s humanism. Which is enough really to make this performance self-recommending.

On 6th September Haitink officially conducted his final performance. After this farewell, classical music listeners will surely miss one of the last truly great conductors, coming from a previous generation that showed a real depth of understanding for the great Masters’ music. Perhaps Haitink is one of the very few who have shown total respect to music by carefully and selectively adopting elements of period performance practice, without sacrificing the composers’ intent.

He has recorded the 9th several times and, for me, the LSO live recording should not be missed, mainly because of the white-heat intensity in all four movements. But I find the present release important for other reasons. In fact, when it comes to this new recording, one can conclude that it brings two unique qualities together: First, you can tell this is a thinking man’s 9th. Second, it is also that of a humanist. This is not a 9th that is defined by the driven passion and, dare I say, the frenzy of the historically informed practice movement – if that’s what you’re looking for, there are plenty of other recordings that offer these qualities. But it is a gracious, humble, solemn statement, full of humility, on one of the greatest achievements of mankind, coming from a conductor who has already entered the pantheon of the greatest exponents of classical music.

* A star rating does not apply to this recording. To rate one of the last recordings of this great musician from a scale from one to five would be nonsensical and a disservice to the wealth of experience we have gained from this conductor. Let us keep our star ratings for the younger generations of conductors for whom I wish Haitink can be a role model of musicianship.