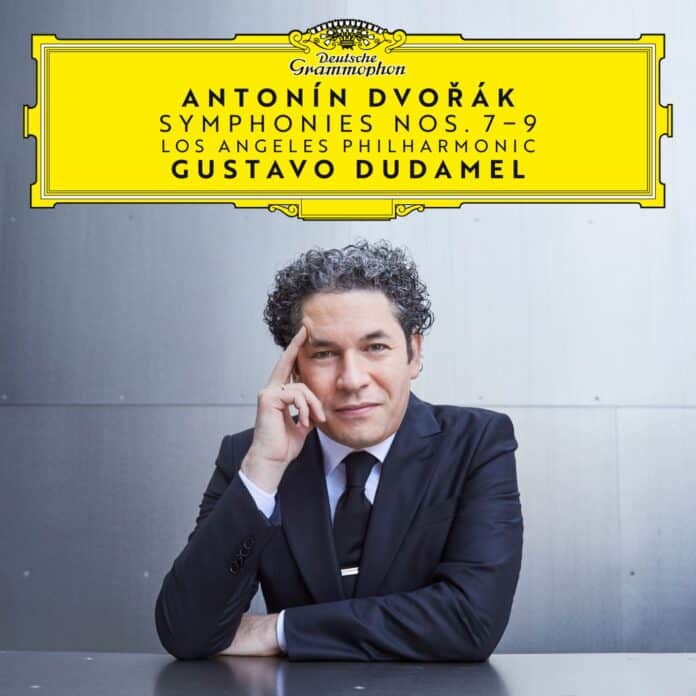

Review – Dvorak Symphony 7, 8, 9, Gustavo Dudamel / Los Angeles Philharmonic / Deutsche Grammophon

Dvorak Symphonies 7, 8, 9 by Dudamel and the Los Angeles Philharmonic – An odd introduction

Earlier in his career, Dudamel had the misfortune of being labelled as a young prodigy. Why a misfortune? Because unfortunately, there are those who perceive wunderkinder with a raised eyebrow — an altogether irrational belief with no real evidence to support it. Off the top of my head, I can think of at least five such musicians, alive today, whose quick rise to stardom placed them in an unfortunate position in the mindset of a certain elitist audience – the audience’s loss for sure. And for those people, please forgive me, but the coach in me wishes to ask you these four questions:

- What is your resistance to musicians who were “discovered” and marketed earlier on in their career (the so-called wunderkind musicians)?

- How has their music-making changed over time?

- How do their recordings compare with other recordings of the same works when you make an unbiased comparison?

- If you are still resistant to their music-making, what does this resistance tell you? What comes up for you?

The actual review

But enough with the coaching that no one has asked for. Now, let’s get to the current recording. Dvorak’s final three symphonies are among the most lyrical works in the symphonic repertoire – few people would disagree with that. And all I can say, in a few words, is that Dudamel’s renditions are extremely lyrical, mature, insightful, and rewarding. I’ll even go so far as to say that we haven’t had such in-depth readings of these works in years.

I’m not going to analyse each movement of each symphony separately, as I usually do in my reviews, because the end result here feels so organic, yet so fresh and new, that a typically structured review would contradict the spontaneity of the music-making here.

First and foremost, Dudamel’s take is both bold and lyrical. He doesn’t subscribe to the cautious–drama approach that is so trendy these days. Instead, he unleashes the full forces of the LA Philharmonic when required – be it the climaxes or the energised outer movements. What is more striking, though, is how he handles the quieter parts.

The conductor is not afraid to take full liberties with the score, so expect to hear carefully judged rubatos (a paradox, I know), diminuendos, and tempo fluctuations. When he slows down significantly for the second theme in the first movement of the 9th, for example, the shock of a new world revealed is more than welcome: at long last, this frequently performed work sounds more bucolic and Slavic, far removed from the soundtrack-influenced idealism of most other performances.

Then listen to how Dudamel lets the winds flow so weightlessly in the 7th’s Poco Adagio slow movement, the melodic lines so clear and natural without being overdrawn.

While listening to these recordings, one conductor’s approach came to mind: that of Kubelik. Yes, Dudamel might lack Kubelik’s pinpoint accuracy, but his overall vision and folkloric sound display complement the latter’s style perfectly.

But this review would be incomplete if I didn’t draw your attention to the orchestra: for it is common nowadays to hear unremarkable, albeit flawlessly executed, orchestral performances. We could once hear a recording and say, “This must be the Chicago Symphony Orchestra,” or we could easily distinguish the oppulent sound of the Vienna Philharmonic (well, in this case, we still can!). My point is that many recordings nowadays sound the same in terms of orchestral texture and character: while in the past the orchestra used to be the primary performer, along with the conductor, it now usually takes a back seat. But not in this case.

I can say, and I really want to emphasise, that the Los Angeles Philharmonic is in a league of its own. This has also been the case with other recent Dudamel releases (for example, the magnificent Ives set), but here they simply outdo themselves. This is not only Dudamel’s game but also the LA Philharmonic’s. It is difficult to single out specific parts, but, as examples, I can mention the precision and ferocity of the scherzi, particular that of the 9th, the melancholy winds in the 7th, or the virtuosity of the brass in the brass-driven craziness of the finale of the 8th. Most importantly (and also a curious thing) is how Dudamel has managed to produce such an Eastern-European rustic sound from an orchestra that some people have wrongly associated with Hollywood.

This is not your middle-of-the-road Dvorak. If you are unfamiliar with these works, you may want to start with a recording that sticks to the score. However, if you know these beloved symphonies and are looking for bold brush strokes, big-toned and romantic gestures, Slavic lyricism, and reflective insights, this is the real deal. Dudamel defies stereotypes once more. And here is a world-class orchestra that outperforms the vast majority of most other world-class orchestras.

And, lastly, to briefly comment on the recorded sound – it’s as good as it gets! Every detail is audible with just enough reverb to make the soundstage realistic without muddling those sharp timpani attacks (especially in the 9th!)