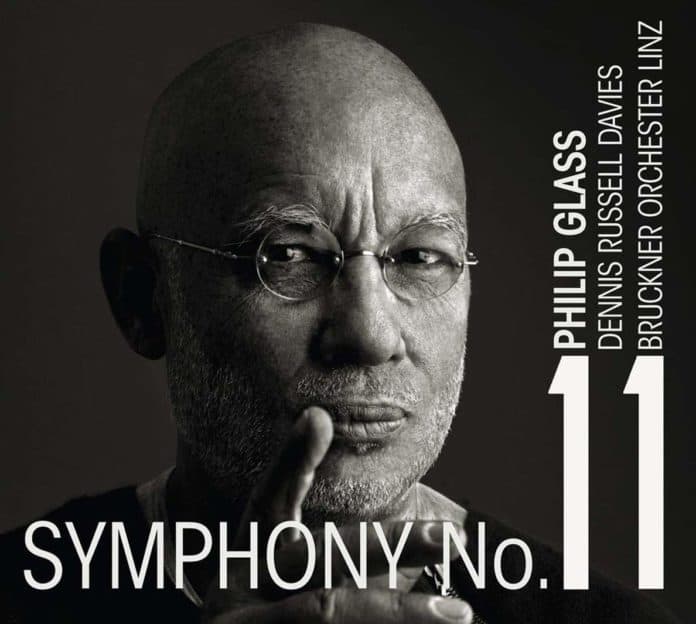

Philip Glass, Symphony 11

Bruckner Orchester Linz

Dennis Russell Davies (conductor)

Orange Mountain Music

Philip Glass, the non-minimalist composer

In my review for the Ólafsson album of the Philip Glass Etudes, I noted how, in only a short period of time since their publication, there have already been 13 different recordings of these pieces. For a composer of such a vast output this might seem reasonable, after all he has composed 11 symphonies and more than 20 operas. But I don’t think this is the case. There are other contemporary composers who are even more prolific, yet very few of their works are being performed or recorded. What is telling about the music of Philip Glass is how high-profile recording companies and renowned artists have been tackling these works.

More importantly, the very fact that the younger generations embrace this music so enthusiastically should give a warning to the naysayers (and there are plenty) of Philip Glass’s music. His music has been described as minimalist despite the composer’s ongoing refusal of this term for his recent works (the booklet notes for the 11th Symphony assure us that his minimalist phase ended in the mid-70s). So, perhaps it’s high time we got rid of such stereotypical descriptions.

Another thing that detractors like to complain about is the repetitive nature of the music. What if the composer quotes his previous works now and then? Isn’t this very fact a mere signature of his compositional style? Or a sign of originality on its own? And since when is repetition thought to be a negative trait?

Well, the critics of Philip Glass’s music have to listen to the composer’s late output more closely: only then will they realise that, yes, there are arpeggios, ostinatos, trills — things that could give the impression of recurrence. But as far as the thematic repetitions are concerned, the discerning listener should notice that, in fact, under the right interpretation, no two repeats in a Philip Glass piece sound the same (as say, they do in the classical sonata form movement or in popular music).

So when, after a Philip Glass article, you come across the reader comments mentioning repetitions take this with a grain of salt. To claim that his music is repetitive or minimal (or boring even) is a fad that has been going on for way too long: it may sound cool to say it out publicly but, in reality, it is clueless.

The 11th Symphony

But enough with the virtues of Philip Glass’s music. I would urge any sceptic to start by listening to the composer’s late symphonies, like the 9th or the 11th which here receives its premiere recording. It is an ambitious work, commissioned by the Bruckner Orchester Linz, Istanbul Music Festival and the Queensland Symphony Orchestra and premiered at Carnegie Hall on 31st January 2017. At the premiere Dennis Russell Davies conducted the Bruckner Orchester Linz: the same forces have recorded the piece for the present CD on the Orange Mountain Music label.

Cast in three movements, at 40 minutes it is a relatively short symphony but with plenty of drive and rhythmic outbursts that often attest to the work’s bigger than life qualities. Take the first movement for example. The main theme is so arresting in its explosive nature that, when it appears for the first time, it’s all the most impressive. What characterises this symphony are the elements of thematic multi-layering of sections and the contrapuntal writing. And even though this description could put some potential listeners off, the way the composer handles these complex layers results in a very musical language indeed.

The first movement begins with a hesitant, dark march: low brass in a mysterious conversation with the strings in what sounds like an introduction pregnant with expectations. When the snare drum section keeps retreating one is left wondering where this is going to lead. A full development of the rhythm is expected but instead of that Philip Glass lets the main theme explode: waves of furious, volcanic string arpeggios and blazing brass, followed by a second more bouncy theme, in Glass’s familiar style of intertwined chord progressions and multiple rhythms. The militaristic sounds are evident throughout, although subdued, and when the movement ends in a march similar to that of the beginning, one realises the narrative element that had been attached to it all this time. In the end, the drama is over. As if returning to the routine of everyday mundanity.

All these turbulent sounds succumb to the ethereal qualities of the second movement, with its dream-like introduction. If the first movement could be described by this reviewer as a dramatic emotional statement with all the noise encapsulating the zeitgeist of our times, this second movement is an attempt for inner peace. Still, there are moments where one senses the undertones of the tension that is about to come forward. And indeed it does, as the movement develops into a game of quiet vs loud interludes that follow each other. Only when the strings and harp enter once more, just like at the beginning of the movement, a hint of an actual ending is given. Whether this is a gesture of farewell or solace will be a personal thing to judge.

As for the third movement, it seems that there is a background story to it. In a YouTube video, Dennis Russell Davies tells us how Philip Glass was not satisfied with the finale when he heard the Bruckner Orchester Linz during the rehearsals sessions and decided to re-write parts of it. The final product is different from the remaining symphony in that the movement begins with some heavy percussion (the work calls for 9 percussionists in total) that is present throughout and its role is crucial: While the brass plays themes that sound familiar from the previous movements, the percussion instruments keep interrupting these in what are part-exotic,

On a final note, kudos to Dennis Russell Davies for having championed the music of Philip Glass all these years. According to the booklet notes he has premiered all of the composer’s symphonies apart from one. The Bruckner Orchester Linz rises to the occasion with impressive playing from all sections of the orchestra — after all, this has also been the case with their previous Philip Glass recordings.

When all is said and done, what we are dealing here is a substantial piece of contemporary music. To place it under the minimalist genre would undermine this fine work. In an interview in The Guardian Philip Glass stated that people don’t believe that he writes symphonies. This could be true for a number of reasons, the first that springs to mind